Subscriber,

Last week we examined how the Graham approach works in a crash. Today we’ll look at how his protege, Warren Buffett, navigated a market calamity twenty-five years ago.

If you don’t feel the urgency, here’s a data point being circulated by Deutsche Bank: for the first time since 2001, aka the midst of the dot-com crash, the benchmark S&P 500 has had more of its stocks fall than rise for nine days in a row.

But this morning I’m remembering 2006, the year I started work on a documentary called Maxed Out, which was borne of an informed suspicion that the white-hot financial industry was about to collapse unsustainable because the laws of mathematics had not, in fact, been suspended to make the stock market go up infinitely. To pay for low six-figures’ worth of music licensing fees (David Bowie, Coldplay, etc.) in this film, I wrote a book of the same name, which was published by Scribner in the US, HarperCollins in the UK and other publishers in Asia. The documentary was distributed by Showtime, Magnolia Pictures and Netflix. For whatever reason, it also became a hit on Singaporean television.

Both Maxed Outs were released in March of 2007. Within a few months, the US financial system was visibly buckling. Coincidence? Maybe. Still I feel compelled to share that those old feelings—the tenseness in the upper back and the fitful sleep, borne of an inability to square market behavior and/or political posturing with reality—have returned, not unlike animal spirits maybe.

Thus my dog has fled to the guest bedroom though I’m comforted by the knowledge that the Graham approach also tends to ancitipate crises. Warren Buffett, for example, got out of the market in the late 1960s before a major correction. (The man he chose to take on his clients, Bill Ruane, promptly lost 50% of their money before a dramatic correction that ultimately made Ruane more successful than Buffett, at least in terms of percentage returns.) These days Buffett is sitting on nearly $350 billion in cash. I’m guessing that the Oracle would deny he’s anticipating a calamity but the Graham approach has prepared him for one nonetheless. Because when the market no longer makes sense, which is another way of saying that it has become hopelessly corrupted (by wishful thinking or financial engineering or sleazy behavior, or all of the above) discomfort is the result. To the rational analyst at least.

Since this Spring, I’ve been writing that current market behavior rhymes with 1999. (This has also been part of my Fund pitch, which hasn’t worked very well, go figure!) As prices have continued upward, I’ll revise my analogy to a conflation of 2000 plus 2008, meaning simultaneous asset and debt bubbles.

How so? Excluding oil, every metric of asset pricing is at or near an all-time high, wiping out the reliable (and necessary) risk premium. Margin of safety? Forgetaboutit. Junk and quality are now the same thing, sometimes by design because good debts and sketchy ones are being comingled into the same security, which gets to assume the rating of the highest quality component, as so backwardly and disastrously happened as the mid-2000s bubble inflated. By the way, when I say “bubble” I mean an environment in which, generally speaking, prices are either arbitrary (bitcoin, gold, real estate, vintage Ferraris, duct-taped bananas) or else yield is below that of a risk-free investment, e.g. the 10-year Treasury Bill.

Everything bubbles are self-complicating. If this was just 2000, for example, and we subbed AI for dot-com, the investor could just stay away from tech companies in general and Elon Musk in particular, though gritting their teeth as day trading neighbors and friends hooted and hollered. But then there’s that twin bubble in debt, including low-yield Treasuries and bad commercial loans that have not been marked to market as well as the aformentioned securiized stuff, which is getting sold and eaten up like candy. Bubbliciousness in all asset classes implies a broader pain than in 2000 or 2008 even. You may recall that the “tech-heavy” NASDAQ fell 80% from its peak in 2000, while the S&P 500 “only” lost about 40% of its value from 2000 to 2002. Now we have a much higher concentration of AI/Musk-related stocks in the benchmark as well as financial engineering landmines planted in the balance sheets of nearly all large companies. I’m guessing that Buffett unloaded most of his Apple stake this year because he didn’t want to be around when the $100 billion that Tim Cook et al borrowed in order to juice EPS and pay Buffett juicy dividends resets at a higher rate. When the tide goes out, you see who’s naked, sayeth the Oracle. Well, the tide is already being pushed out by higher rates, and not by a little.

The tsunami cometh. Consider TSLA, which this weekend trades at a forward yield of 0.7% and pays no dividend. Tesla’s earnings per share would have to grow by around 500% just to get it back in line with the rest of the S&P 500, which is trading near historic highs vis-a-vis earnings. Last quarter the company’s sales grew less than 8%, year on year. Then there’s Costco, which is yielding less than 2% with a dividend of less than one half of one percent. Costco is also growing sales around 8% per year. Its EPS would have to grow about 200% just to get back to benchmark pricing, and more than that to settle into historical price levels. Assuming Costco can keep growing at 8 percent, that will happen nine years from now, in December of 2033. It plans to increase store count by less than three percent next year. Id est, Good luck, babe.

Then we have the AI contenders, like Amazon and Oracle, for example. Their earnings seem fine but cash flow has evaporated thanks to the GPU Rush. Participation is mandatory. Last quarter, the mighty Amazon produced only a trickle of a couple billion in cash while Oracle’s free cash flow went negative. You gotta pay to play, I get it. But some day, all of those capitalized GPUs will be expensed, probably as a “one-time” charge, as newer and better models arrive every year. Will investors accept this accounting sleight of hand? Maybe.

Another bit of creative accounting: the two trillion dollars borrowed by the United States Treasury each year is still counted as GDP growth. More than half of that amount is now expensed as interest each year, which is also counted as economic growth. Which dwarfs actual economic growth.

But no one cares about the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet. Back to the market double bubble, then, which is even scarier than it appears. Why? A marked deceleration of corporate revenues—or cadence, as the Wall Street analysts like to say. Tesla was doubling its sales every year and Costco’s stores were averaging double-digit gains not so very long ago. Now they’re in mid- to high-single digits territory. If this cadence continues—or if sales growth freezes at current levels—well, someone who matters is bound to say that the emperor has no clothes and even the hooters and hollerers will be inclined to take notice.

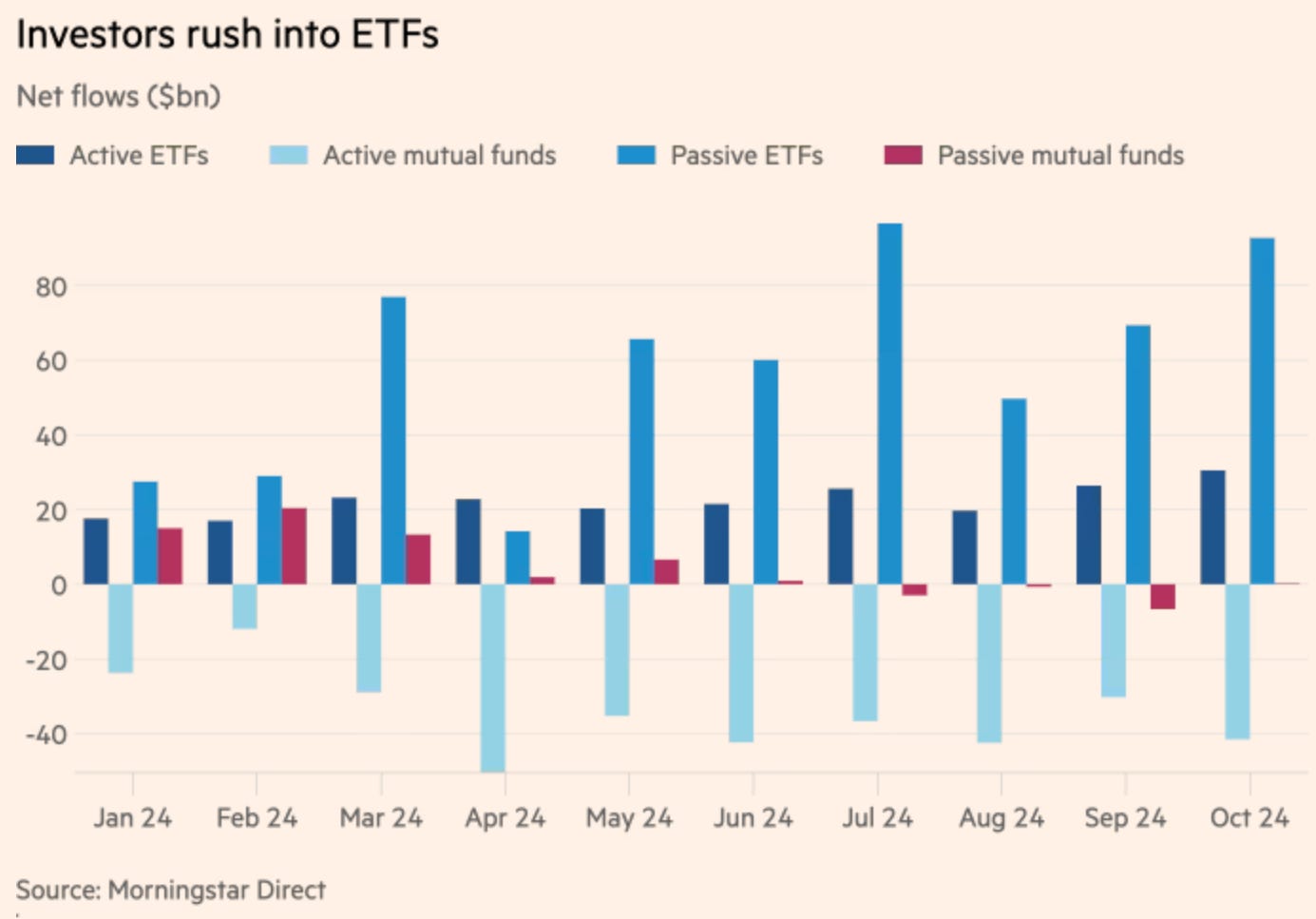

Also, the great melt-up has been leveraged not only by the financial engineers but simultaneously by the dumb money. (Synergy!) While the margin debt that fueled the first wave of this bubble has come down slightly, the popularity of highly leveraged single-issue ETFs (see below) and EPIs, among other things, has hidden the true amount of debt propping up prices. Nothing keeps the music playing like ignorance but I digress. Let’s see what happened to the Graham approach followers in the dot-come crash—and what will happen this time around, probably.

The first column is the price performance of Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.A); the second is the S&P 500’s.

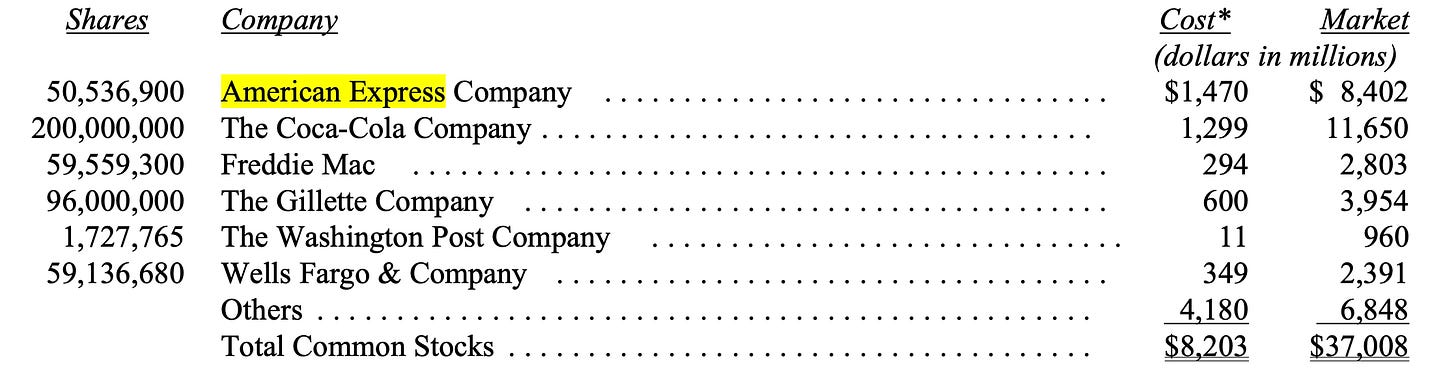

You’ll notice that Berkshire’s awful 1999 loss foreshadowed the calamity to come. Not shown is the considerable grief he received from shareholders who wanted him to get in on the dot-com action that year, i.e. the height of the bubble. If you’re curious, here’s what the company’s portfolio looked like at the start of 2000, when I myself was moving my family’s money out of stocks and into “risk-free” GNMA bonds:

As the bubble (inevitably) deflated, these boring old-economy stocks over-performed. Between 2000 and 2007—the year of Maxed Out’s release and one year before Lehman Brother’s declared bankruptcy—Berkshire Hathaway gained 125% whilst the S&P rose just 14%. (Dividends would have pushed the benchmark up around the 20% mark, but the gulf remains monumental.) I think it’s worth noting that, in early 2001, Buffett told his investor-partners that these investments were fully priced, which turned out to be prescient. How many CEOs these days are stating the bubbly truth? None that I know of. But this quarter, I’d estimate that roughly 100% of CEOs have bragged about buying back lots of their own shares, the more the better, with their invesors’ money of course. So everyone’s on the same page, yet those of us past a certain age know how this story ends.

But, but…Trump-Musk will release the animal spirits! croweth the bulls, much as they did in 2000-1, then with Bush-Lay as the twin CEO saviors of animal spirited capitalism.

The other bullish argument is that investors will always buy stability, which is supposed to favor the US markets to infinity and beyond. But this not only ignores price, it glosses over the fact that Trump-Musk is selling disruption—if not yet delivering it, like South Korea. I’ll note that countries like Spain and Greece that allowed their financial crises to play out are now among the most stable economies. Meanwhile, China’s real-estate crisis seems to be cycling out. A reliable rule of post-bubble markets is this: No pain, no capital gain.

In other words, investors who are managing huge sums or who are not prepared to be very active should probably get out of the trading business, while those who manage lesser sums, and who are willing to be patient and agile, will find themselves doing a lot of work to do okay. Also looking at places like Ireland and Australia.

A final scare: as in 2000 and 2008, millions of Americans are relying on the asset bubble to make ends meet, in addition to their credit cards. Those without financial assets seem to be doing terribly. So it is that the hottest commodity these days is cheap food—which, like expensive assets, tends to create a brief high followed by a long period of remorse.

James

p.s., I’m trying to decide whether to continue publishing this into next year or converting to an internal memo for my partners. The more paying subscribers, the more likely the newsletter is to continue. If you find it helpful and would like to read more, please click on one of these buttons (or both!):

Intelligent Fund inquiries: e-mail savannahcorp@yahoo.com.

go birds