Subscriber,

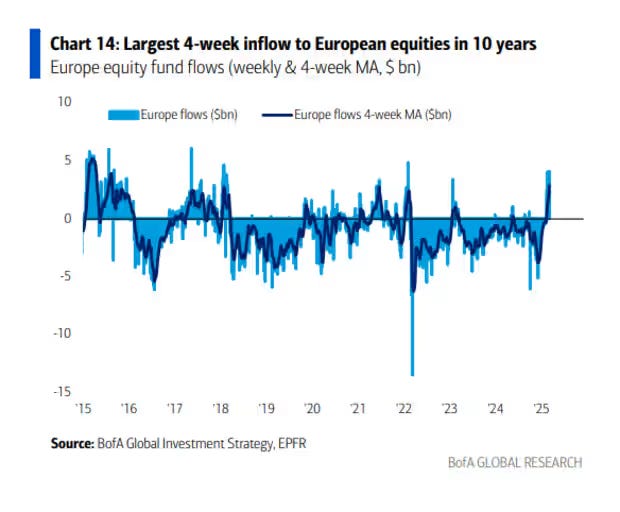

In case you needed convincing, the past week has proved tariffs will not make us rich, indeed they erased huge amounts of wealth here in the United States while stock markets in Asia and parts of Europe gained. In a week defined by yo-yo tariffs, US stock markets lost over a trillion dollars of paper value. The benchmark S&P 500 fell three percent, the NASDAQ somewhat more, while the UK’s FTSE 100 lost just 1.5%; the Hang Seng (Hong Kong) gained 5% and Germany’s DAX was up 2%. And it would have been much worse if the Fed Chairman had not intervened on Friday with a pep talk. Oh, and the US trade deficit, that wealth-killer that the President aimed to vanquish with tariffs, jumped 10% to $270 billion in January. Irony, Trump is thy name?

Not to brag about noticing blinding glimpses of the obvious, but our decision to heavily internationalize Portfolio 8.0 is looking prescient and paying off handsomely. The next update is two weeks from today—if you aren’t tracking it on your phone already, which, of course you are. Moving on…

That the international investor need be some kind of geopolitical expert or at least possess (read: borrow) a fully-formed worldview is a notion and not reality. Because the same thought leaders and media that sell expertise and worldviews frame every market event, including the shift away from American markets, as some kind of political phenomenon. But if this were so, political scientists would be billionaires. Instead, it’s an overcomplication, by which I mean the experts are rationalizing rather than reasoning. If they shifted their own perspective, they would see a blindingly obvious reason for investors to look to Europe and China and Australia and other markets right now, which is that they offer yields far higher than the U.S.’. And yield is the only thing the investor should care about in a stagnant economy; indeed the first graph above illustrates just how far over their skis US investors have gotten recently, largely by assuming that historic growth rates will continue ad infinitum. The intelligent investor, on the other hand, asks, Why buy into inevitable pain and suffering? Why not make money whether animal spirits return or whether, as the Treasury Secretary stated last week, the economy will be in “detox” for some time?

I’ll tell you why! But first two observations from my review of all of the NASDAQ and New York Stock Exchange-listed companies, ex-banks, real estate and airlines, which is now complete. Caveat: I only look at numbers.

Number one: prices tend to self-correct eventually, and the higher the inefficiency (or the more speculative) the greater the correction. See: Tesla, Palantir.

Number two: the noise about consumers being maxed out is validated by earnings data. Maybe it’s fear of tariffs or long Covid, or more likely the Covid break—during which time many got a couple of small government checks in the mail and others were spared making payroll for six months or so; in return they got to deal with higher prices and interest rates forever—just delayed the inevitable.

I experienced this firsthand, and painfully, when I bought shares of the boatmaker Mastercraft for my fund in late 2023. Anything marine-related then looked like a fire sale, and Mastercraft was on solid financial footing and it’s a terrific brand. Before Covid it also happened to be durably profitable. But istead of bouncing back with the stock market and interest rates that rewarded its target market (folks with money market accounts) Mastercraft waited in vain for its dealers to place new orders, then buttoned down the hatches and sold off an operating division. There’s a similar narrative at Harley-Davidson. Corporate recruiting companies and, increasingly, retailers that are not bargain basements are also lagging. Last week even Costco disappointed while Target and Wal-Mart warned and multiple chain restaurants catering to the middle-class went bankrupt, following Red Lobster’s lead. Providing high quality experiences or goods at low prices just isn’t happening these days; instead it’s high prices and meh, which is not a recipe for stimulating a consumer economy.

(A third observation from my analysis: lot of formerly great companies are scrounging for a new business model, as in something more substantive than “internalizing” AI.)

Stagflation has been discussed here for well over year and now it has entered the public discourse, though it’s still treated with such trepidation, maybe because it doesn’t help sell risk assets, I don’t know. The obvious white knights, aka the AI IPOs, are not evenon the horizon yet, if they come at all, so private equity has turned to buying junk debt and boring old insurance companies while activist investors are urging their targets to juice earnings with invisible coins because that worked last month or because Trump held a crypto conference or whatever. This leaves wealth managers and their customers with an intractable problem: they have no idea what their holdings are worth, and this has become an imminentl problem without growth to smooth over mistakes (or as misdirection) and lots of greater fools to pay ever greater prices. What ever will they do now? one wonders.

Yesterday the chief strategist at a large retail brokerage that will remain nameless, provided the answer: nothing. There will be no change of course because passive investing has worked in the past, saith she, and markets always go back up eventually and so on and so forth. On Monday her words will echo in thousands retail investing offices around the country, and her competitors will of course tell their customers the same thing: everything is awesome—not now oof course but in the long run! To them I give the closing price of the NASDAQ Composite on two dates not so long ago:

January, 2001 4,572.83

July, 2015 4,620.15

Net-net: the favored stock exchange of innovators went fourteen and one-half years with no appreciable growth and almost nothing in dividends. Which proves that to be a passive investor you have to be very good at timing, which no one really is. Which is why, as Ben Graham observed, the only guarantee of outsized returns over time is to price individual stocks rather than time the market.

As a quantitative investor, Graham ascribed to the truism that past is prologue. Ironically, the financial industry does too—but only when it applies to markets and almost never to individual stocks. This is the original sin and its consuences are two-fold. One, market timing divorces people from the idea of value, encouraging a fixation on arbitrary price movements. This portends armies of highly-educated forecasters, er analysts, whose job is to predict the future in various ways, whether an established company’s upcoming earnings or the technology of the future or the effect of Elon Musk’s political activities on sales of Tesla EVs or the price of an invisible coin five years from now or whither inflation and/or interest rates and on and on and on. This army of analysts, not unlike the army of bros who gossip and debate at network desks or on the Internet during whatever sports season, engages in fools’ errands that Graham argued cancel one another out at the end of the day, yet they are also a major selling point for brokerages, investment banks, hedge funds, private equity firms and on and on. So the message is conflicted: yes, past is prologue when the market is down (never sell!) but also it’s the future that really matters and therefore you really need the smarest people in the room on your team, don’t you, even if they are doing something kind of stupid. Which is why the late Charlie Munger admonished that things that weren’t worth doing still weren’t worth doing well. But he knew the exception, which is when you’re getting paid to do so.

Why care about any of this?

Because the intelligent investor’s competitive advantage is to know the one thing that all of these anlaysts never get around to calculating: the intrinsic value of what one is told by the analysts is a buy (almost always) or sell or hold or conviction hold or whatnot. If they are feeling bold, or if their customers need a visual, these analysts might issue a “price target” but this is more conjecture than past-is-prologue. A car salesman never tells you what all the parts are worth, do they, it’s the intangibles that make something, or maybe everything, priceless. But the new car smell of success has tended to fade fast, even for cannabis stocks and other sure things. So it is that we’ve scooped up a number of cigar butts but no joints—and we won’t, at least for the next ten years, and only if they start making money right now. (Always go low, never high is my motto.)

On a positive note, last week China committed to 5% economic growth again this year, the European Central Bank cut interest rates and the new German government implied they will borrow whatever it takes to get back to growth mode. (If you’ve seen the new Volkswagen Bus EV you may have tempered your enthusiasm however.) Also, I foraged seven more investables (after the paywall), only one of which is a growth stock, meaning a yield below 10%. Which is important because it is much easier to value yield than future growth, which is why the Graham method tends to overperform when the economy, and the market, lags.

In order to get the reader away from sin and prime the pricing-not-timing/do-it-yourself pump, I’m offering every paid subscriber two quantitative valuations per month. Just e-mail the ticker symbols to savannahcorp@yahoo.com and you will promptly receive their quantitative (intrinsic) values, per share, and per Benjamin Graham’s methodologies. You may use this as a fact-check of your own research or treat it as the gospel truth, just remember that quantitative value is simply the value that can be demonstrated by past results, it does look forward to future events or consider assets that have not produced profits or cash flows. So it’s not an immaculate conception but it is consistent.

Also, I’m working on a kind of Cliff’s Notes of The Intelligent Investor for those of you who have tried so hard to read Graham’s book but just couldn’t get past the archaic prose and dated case studies and sometimes the first two paragraphs. This will also be available free of charge to paying subscribers soon.

Passive is past tense. It’s time to crunch..

James

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Intelligent Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.